The processes involved in taking an idea or result to the market are quite varied and poorly understood and so are the steps academic institutions and companies are taking to bridge the gap. The conference on the Economics of Innovation held in September 2017 in Geneva provided insights on the matter. Prof. Anja Schulze, University of Zürich, reports on the session devoted to industry-academia relations and highlights the major conclusions.

The idea of a “gap” between research done in academia and its translation into marketable products certainly is not new. The efficient translation of scientific discovery into innovative products that benefit society is a major goal of many countries, in particular those without substantial natural resources. However, the processes involved in taking an idea or result to the market are quite varied and poorly understood and so are the steps academic institutions and companies are taking to bridge the gap.

Industry – academia relations

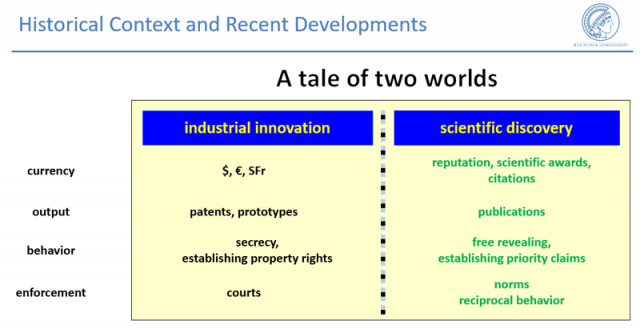

Many innovations that have found their way into economy and society are rooted in scientific discovery. However, as Prof. Dietmar Harhoff (Director at the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition) points out, translating scientific knowledge into innovation and the industrial domain is challenging as such translation needs to combine two complementary worlds that are very different in nature, namely the academic and the industrial. Both worlds are subject to distinct governance structures (Figure 1). On one hand, there are academics who conduct research with the objectives of publishing in top tier academic journals and recognition. On the other hand, there are business organizations that develop and commercialize innovative products and services with the objective of competitiveness and profitability. Although, in some cases, research in industry may allow for publication and university research for patenting, the two worlds continue to stand largely apart.

Figure 1: A tale of two worlds (source: presentation by Prof. Harhoff)

A set of presentations and discussions at the conference pertained to approaches of bridging the worlds of academia and industry whereas two approaches evolved: maintaining specialization and using brokers or moving towards generalization and reaching out to the other world.

Specialization and using brokers

Universities and firms stick to their core capabilities, namely research and teaching (universities) and commercialization (firms). To bridge the gap, they rely on third parties such as Technology Transfer Offices that act as brokers. Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) have been installed by Universities to help researchers to disseminate newly developed scientific knowledge for the purpose of inducing industrial applications and innovation in the market and to benefit society. As Amir Naiberg explains, the scope of TTOs activities includes the establishment of links to knowledge users (matchmaking with firms), commercially evaluating new technologies, determining patentability and commercial value. On other words, TTOs provide academics with insights into what ideas may be commercially valuable. Further, TTOs prosecute patents, marketing and licensing inventions but also facilitate the founding of faculty startups. In sum, TTOs facilitate knowledge transfer which often pertains to technological knowledge.

Generalization and reaching out to the other world

Often, translating scientific insights for their dissemination and matchmaking with firms that are potential knowledge users is insufficient as scientific knowledge is far from readiness to application. It needs continued development and transformation. This is can be attained in two ways, whereas both ways include the creation of interlaced skills and knowledge. That is both, industry and academia broaden their knowledge and capabilities and, thus, generate an overlap of their worlds.

On one hand, academic scientists’ push the scientific knowledge towards the market by actively engaging in its transformation (i.e., navigation towards its applicability), and in commercialization activities. Scientists found companies with the objective to commercially exploiting a patented invention, or in some cases, a body of unpatented expertise. However, such knowledge or technology push is individually driven and pursued on a discretionary basis. It depends on the independent initiative of academics, such as Kai Johnsson. Moreover, young researchers will be evaluated based on the incentive schemes of academia, namely publication records. Hence, mainly established scholars engage in founding science based start-up companies.

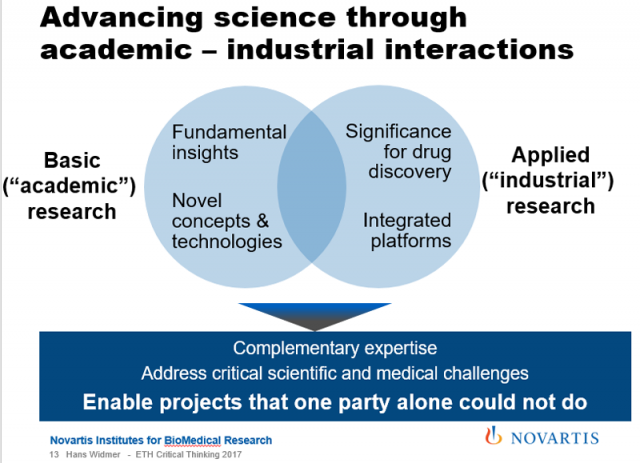

On the other hand, the industry pulls scientific knowledge from academia. For example, firms engage in knowledge-related collaborative research projects with academia. For this purpose, they develop longer term partnerships that are usually strongly based on ‘person-to-person interactions’. Often, companies assess such research collaborations as more valuable than licensing university patents, as Dr. Hans Widmer from Novartis emphasizes.

Figure 2: University-industry collaborations (source: Presentation by Dr. Widmer, Novartis)

Finally, scientific disciplines differ in their extent of direct knowledge transfer from university to firms. Prof. Thursby has studied many fields within the scientific disciplines. The more applied fields of research, such as engineering or computer sciences engage most in the commercialization of their knowledge and in creating entrepreneurial ventures. Fields such as physics, biology and medicine, while having enormous impacts on eventual applications, tend to have their knowledge transferred with longer time lags and much more interaction with established companies. And researchers in mathematics and social sciences, again having tremendous impact of society, follow a different path. A higher proportion of their knowledge can be thought of as a public good, disseminated through students and open publication.

Related literature

Perkmann, M., V. Tartari, M. McKelvey, E. Autio, A. Broström, P. D’Este, R. Fini, A. Geuna, R. Grimaldi and A. Hughes, Academic engagement and commercialisation: A review of the literature on university–industry relations, Research Policy (2013).

Presenters

- Prof. Dietmar Harhoff, Director at the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition, Munich, Germany.

- Prof. Kai Johnsson, Full Professor at the Institute of Chemical Sciences and Engineering, EPF Lausanne, Switzerland. Former co-Director of the NCCR Chemical Biology. Director at the MPI Heidelberg, Germany.

- Mr. Amir Naiberg, Associate Vice Chancellor, Chief Executive Officer Technology Development Group and Chief Executive Officer & President of Westwood Technology Transfer, UCLA Technology Development Group.

- Prof. Marie Thursby, Regents’ Professor Emeritus of Strategy at Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia, USA.

- Dr. Hans Widmer, Program Director at Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Switzerland.

Anja Schulze is Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Professor at the University of Zürich. She works in the field of Technology and Innovation Management and she is heading the swiss Center for Automotive Research (swiss CAR) which conducts and publishes industry studies on the Automotive (suppliers) industry in Switzerland.

Leave a comment

The editors reserve the right not to publish comments or to abridge them.